April 2017 | Volume XXXV. Issue 2 »

Data Back Up the Headlines: Adding Weight to Advocacy

March 23, 2017

Michelle Guittar, Northwestern University and Kelly Grossmann, Eastern Michigan University

Since 2010, a growing number of headlines have hinted that support for school libraries in Illinois has been on a downward trend. A few examples:

- In October of 2010, the Chicago Tribune reported the “CPS library void transcends one sit-in: Lack of money, space forces more than 160 schools to go without.”

- A few years later, WBEZ, Chicago Public Radio revisited the issue: “Losing school librarians in Chicago Public Schools.”

- In 2015, the loss of a school librarian came under national attention when the Washington Post covered the student protest to save the position of Sara Sayigh, a Chicago school librarian at the multi-school DuSable campus that serves Daniel Hale Williams Prep and the Bronzeville Scholastic Institute.

- In 2015, the loss of a school librarian came under national attention when the Washington Post covered the student protest to save the position of Sara Sayigh, a Chicago school librarian at the multi-school DuSable campus that serves Daniel Hale Williams Prep and the Bronzeville Scholastic Institute.

- And then, Sayigh’s position was among those eliminated in October 2016, due to “shrinking budgets and declining enrollment,” as reported by WTTW Chicago Tonight.

- That fall, American Libraries issued a statement on its website, “Speaking out against Chicago school library cuts,” regarding the reduction of CPS library positions.

These individual reports led us wonder if the pattern was a localized issue confined to the Chicago area, or if a similar trend was emerging statewide. We sought broad, quantitative data that could definitively tell us how the funding allocations for educational media services of Illinois high school have changed over time. Through the analysis of budget reports of Illinois school districts, we discovered that, on average, districts with high schools experienced a decrease in funding for school libraries.

MAPPING THE RESULTS

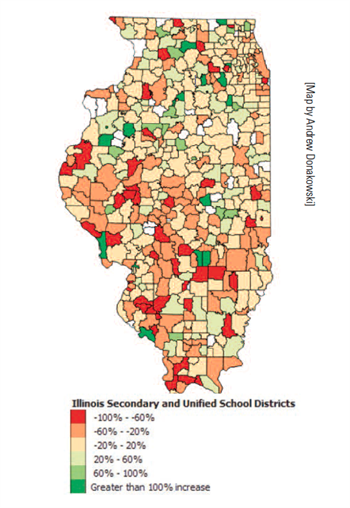

Due to its coverage in the local news, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) may be the district that most immediately comes to mind when referencing eliminated librarian positions or supplies budgets, but school districts downstate have felt the most dramatic cuts to their budget allocations for Educational Media Services (EMS). We worked with Andrew Donakowski, a graduate of Northeastern Illinois University’s Geography and Environmental Studies master’s program, to use GIS to map the amounts of gains and losses to EMS budgets over the four-year time period of our investigation. On the map, the red and orange districts are those that lost percentages of their budgets from 2009 to 2014, while the light and dark green indicate districts that gained percentages of their budgets from 2009 to 2014. The beige districts have remained relatively neutral, at gains/losses of +/- 20 percent.

“Through the analysis of budget reports of Illinois school districts, we discovered that, on average, districts with high schools experienced a decrease in funding for school libraries."

The map demonstrates that the districts south of Interstate 80 have generally seen more severe cuts to their budgets for EMS than those districts on the north side of the state.

ACADEMIC CONSEQUENCES

These changes to EMS budgets go far beyond CPS. And, as coverage on the reduction of school librarians has continued, there has also been an increase in the amount of coverage of

a related problem: students arriving at college unprepared for the demands of college research and not able to effectively evaluate sources. Multiple studies, including those from Project Information Literacy, have found that students are routinely underprepared in their levels of information literacy competency at the undergraduate level. In 2010, Hargittai et al. found that young adults used a variety of factors to judge the credibility of web content, but students often did not investigate who authored a website or look past the first few search results.1

In 2012, Gross and Latham found that self-views of their own research capabilities often did not correspond with students’ actual information literacy skills.2 The Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries (ERIAL) study, which was conducted at multiple Illinois academic institutions including Northeastern Illinois University, revealed that students struggle with basic information literacy skills, including conducting effective searches, evaluating resources, and seeking help from information professionals.3 Students’ evaluation skills have not been improving since these initial studies, even with increasing access to personal technology devices. Most recently, researchers at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education released the report, “Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning,” which evaluated the abilities of students at all levels to evaluate information presented in different kinds of online media, including web articles, tweets, and comments. They found that all students demonstrated a “stunning and dismaying consistency” in their abilities to evaluate information found on the Internet, and summed up those abilities as “bleak.”4

It is clear that these budgetary losses stress librarians at every level: school librarians, whose work environments are under siege; public librarians, who are now asked to also provide academic library resources and training; and academic librarians, who now have the difficult task of preparing students for college-level research when they are already in college. And of course, these losses are directly felt by the students themselves, who may lose access to books, support staff, and places that they keenly adore–-and who still may not be able to properly evaluate web sources upon high school graduation.

COLLECTING BUDGET DATA

The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) currently makes budget data public for school districts throughout the state. At the outset of this project, ISBE provided the most complete budget data for the years of 2009 and 2014, with information available from over 800 school districts.5 Our analysis focused on those districts with secondary schools to gain a more complete picture of the kinds of library environments that theoretically prepare students for college-level research. We found 473 districts with secondary schools that existed both in 2009 and 2014. From the district-level budgets, we extracted allocations data from the EMS line (line 2220), which includes Service Area Direction, School Library Services, Audio-Visual Services, Educational Television Service, and Computer-Assisted Instruction. This budget line is broken down by spending category: Salaries

(Regular, Temporary, and Overtime), Employee Benefits, Purchased Services (includes any services that may be contracted out), Supplies and Materials (includes the purchase of library books and periodicals, as well as binding and repairs), and Capital Outlay (building projects and improvements).6 The budget line for EMS is included under the broader category of “Educational Support Services.” School-level data are not collected by ISBE.

MEASURING CHANGE

We calculated the average EMS budget lines of 473 Illinois state public school districts with secondary schools in 2009, and 491 in 2014. In 2009, the average (mean) budget was $491,827. In 2014, the average dropped to $464,294. Average total budgets dropped by 5 percent, salaries dropped by 5 percent, and supplies dropped by almost 15 percent. However, there is great disparity in changes in individual districts during this five-year time period; slight gains in some districts offset losses in others, with some districts losing far more than the 5 or

15 percent averages.

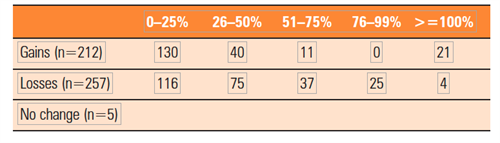

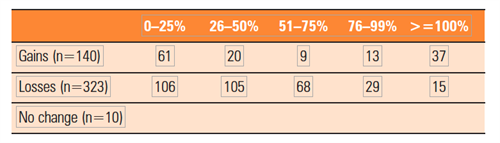

TABLE 1: Changes in budgets for EMS in school districts with high schools, by number of districts (average 5.5 percent loss, 2009–2014)

Overall, in districts with high schools, a greater number of districts lost money from their budget for EMS than gained money. Of the 474 school districts with secondary schools that we could compare across this five-year time period, slightly under half of the districts had gains below 25 percent. More than half of the districts experienced negative changes in their budgets. In 2014, there were 12 districts that had no budget allocation at all for EMS.

Overall, in districts with high schools, a greater number of districts lost money from their budget for EMS than gained money. Of the 474 school districts with secondary schools that we could compare across this five-year time period, slightly under half of the districts had gains below 25 percent. More than half of the districts experienced negative changes in their budgets. In 2014, there were 12 districts that had no budget allocation at all for EMS.

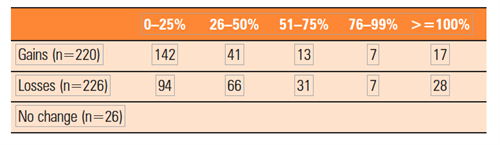

TABLE 2: Changes in salary allocations for Educational Media Services in school districts with high schools, by number of districts (average 4.73 percent loss, 2009–2014)

Salaries, the first budget category analyzed within the total budget allocation for EMS, also experienced a 4.73 percent drop on average, with wide disparities between districts. Slightly under half of the districts saw increases in salary allocations for EMS, with the majority being between 0 and 25 percent. More than half of the districts had cuts to their salary allocations between 2009 and 2014. Seventeen districts added salaries where previously there had been no allocation, while 28 school districts cut their entire salary budgets for EMS. In 2014, there were 63 districts that had no allocation at all for salaries within EMS.

TABLE 3: Changes in supplies allocations for EMS in school districts with high schools, by number of districts (average 15 percent loss, 2009–2014)

Supplies, the second budget category analyzed within the total budget allocation for EMS, had the most dramatic negative changes over the five-year period with an average loss of 15 percent. Most districts experienced a loss to their supplies budgets, with 64 percent of those districts losing up to 50 percent of their supplies allocation. In 2014, there were 27 districts that had no budget allocated for supplies within EMS.

Due to its size, the inclusion of the CPS budget in the calculation greatly inflates the average in every category, therefore the median budget may provide a more accurate representation of the average budget experience for EMS in the state of Illinois. From 2009 to 2014, CPS dropped almost 25 percent from its overall budget for EMS, a total of $11,068,383, the majority of that coming from staffing ($8,196,931), and supplies ($223,793, a loss of 69 percent).7

A reason for this dramatic shift in budgets for staffing and supplies is due to the FY2014 shift of student-based budgeting in CPS, based on enrollment and number of pupils, that also gave principals control over large portions of their budgets (50 percent) that had originally been controlled by the district, including money for core staff, educational support personnel, supplies, and additional instructional programs.8 Student-based budgeting continues to be the funding model for CPS.9 Because ISBE does not collect school-level data for EMS, we cannot know how much its funding has changed within individual Chicago Public Schools. However, even removing CPS from the equation, just 256 school districts with secondary schools still lost a combined total of over$25 million from their budgets for EMS. This is a financial loss that broadly affects all levels of libraries throughout the state.

For this reason, we all must be concerned about the future of high school libraries. The Illinois Library Association (ILA) lays out the key actions for each year, the initiatives worth supporting that will provide for the continued state funding of libraries at every level. Your advocacy, and your professional expertise, are absolutely crucial for the ongoing existence of school libraries—and now there are data that show how crucial that advocacy continues to be.

Note: This research was completed while we were both librarians at Northeastern Illinois University. Thanks to Dave Green, Associate Dean of Libraries at Northeastern Illinois University, Andrew Donakowski, GIS extraordinaire, and for funding this research, the Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois and the Committee on Organized Research at Northeastern Illinois University.

1 Eszter Hargittai, Lindsay Fullerton, Ericka Menchen-Trevino, and Kristin Yates-Thomas, “Trust Online: Young Adults’ Evaluation of Web Content,” International Journal of Communication 4 (2010): 468-494.

2 M. Gross and D. Latham, “What's Skill Got to Do with It?: Information Literacy Skills and Self-Views of Ability Among First-Year College Students,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 63 (2012): 574–583. doi:10.1002/asi.21681

3 Lynda M. Duke and Andrew Asher, College Libraries and Student Culture: What We Now Know (Chicago: ALA Editions, 2012).

4 “Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning: Executive Summary,” Stanford History Education Group, November 22, 2016, https://sheg.stanford.edu/.

5 To give some context to the number of school districts in the state, of the 859 school districts in 2015, just 23 districts served over 10,000 students (3%); 681 districts, the vast majority, serve less than 2,499 students (79%); on average, in 2015 Illinois school districts served 2,399 students per district (Dabrowski and Klingner, 2015).

6 “Illinois Program Accounting Manual,” Illinois State Board of Education, accessed February 20, 2017, https://www.isbe.net/Documents/ipam.pdf.

7 For Chicago Public Schools, there was an additional budget category, Termination Benefits, which is severance pay, and does not appear in the budget reports of any other district. In 2009, the allocation for these benefits was $1,037,818 in 2009 and in 2014, it was $404,536.

8 “Chicago Public Schools Fiscal Year 2014 Budget,” Chicago Public Schools, accessed February 20, 2017, http://www.cps.edu/finance/FY14Budget/Pages/schoolsandnetworks.aspx.

9 “Chicago Public Schools Fiscal Year 2017 Budget,” Chicago Public Schools, accessed February 20, 2017, http://cps.edu/fy17budget/Pages/overview.aspx.

iREAD Summer Reading Programs

iREAD Summer Reading Programs Latest Library JobLine Listings

Latest Library JobLine Listings