September 2025 | Volume XLIII, Issue 3 »

Teaching the Infodemic in Real Time

September 2, 2025

Bradley J. Wiles, Northern Illinois University

Over the past two decades, the rise of social media, mobile web technologies, and an increasingly online culture have presented a seemingly intractable professional crisis for librarians, archivists, and others working in the information fields. We are living through the latest and arguably the most intense iteration of the Infodemic. But what is the Infodemic? The term–a portmanteau of information and epidemic–was coined earlier this century to describe issues associated with information provision during public health crises, when misinformation and disinformation spread with exponential speed throughout populations and complicated efforts to mitigate disasters. It has since been understood and applied more widely to describe a generalized Information Age malady characterized by the pervasive influence of digital information technology in all aspects of personal, institutional, and social activity. As the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated, the cognitive dissonance caused by the various manifestations of the Infodemic have serious implications for citizenship, human rights, democracy, and the physical and mental well-being of a hyper-connected global community.

What are we to do as information professionals? A common response has been to redouble our efforts to promote information literacy in the various venues available to us. To this end, during the Spring 2025 semester I taught an undergraduate course called “The Infodemic: Misinformation, Disinformation, and Conspiracy Culture in the Information Age, 1945–2020” as part of the Northern Illinois University Honors Program. The course was developed around the program’s 2024–2025 multidisciplinary curricular theme of “Reality and Fantasy,” and emphasized the importance of critical thinking and analytical skills needed to successfully negotiate an information technology-saturated environment. In addition to learning how to identify and understand some of the primary components of the Infodemic and their impact on contemporary society, students were exposed to scholarly literature and other resources describing various dimensions of this phenomena.

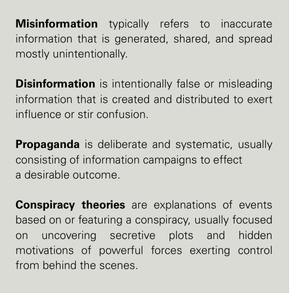

The course focused on some of the primary vectors of the current Infodemic, namely misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and conspiracy theories. There are many other possible Infodemic elements that were touched upon throughout the course (i.e. censorship, intellectual freedom, copyright, algorithmic bias, etc.), but I was most interested in those four because they seem to have incited the greatest amount of anxiety due to what they potentially mean for control and agency over our lives, livelihoods, and institutions. They are certainly among the most sensationalized in the public imagination, because the threat they pose is real, even if the extent of that threat is mostly never realized in its worst forms. But besides that, misinformation, disinformation, propaganda, and conspiracy theories work so well together–they are complementary and mutually reinforcing.

My instruction was partially aimed at helping students develop strategies for mitigating the effects of the Infodemic on their media and information consumption and decision-making, while also giving them the tools to critically assess information sources. Most importantly, my instructional strategy was to encourage students to relate their own experience of the Infodemic in real time, which coincides with the politically and socially tense conditions these young people have known their entire adult lives. The Infodemic course students were tasked with four main learning objectives:

- Identify and critique some of the primary components and characteristics of the Infodemic and the impact these have had on different aspects of contemporary society.

- Analyze and articulate historical factors, political implications, and techno-cultural dimensions of the Infodemic’s development, evolution, and attempts to manage it.

- Develop and implement strategies for mitigating the effects of the Infodemic on their own media and information consumption and decision-making.

- Critically assess information sources and information ecosystems for scholarly utilization, especially writing about complex subjects.

The course was divided into three thematic units that provided the conceptual and definitional foundation of the Infodemic, examined specific historical instances and sociocultural contexts of its main components, and considered its impact on modern democracies and information communication technologies. Although the course was grounded in Information Studies, I employed a multidisciplinary approach that incorporated ideas, theories, and readings from History, Psychology, Political Science, Communications and Media Studies, Philosophy, and Popular Culture Studies. I used multimedia sources where possible and was able to line up several article authors and other subject matter experts as guest speakers to discuss their work or the weekly topic. There were several recurring concepts that emerged throughout the course including information abundance, overload, and entropy, the notion of subjective, objective, and normative truth, and epistemology (how we know what we know) in relation to cognitive authority–or who and what we as individuals choose to trust for second-hand information and knowledge about the world.

Because this course was originally designed as a graduate LIS seminar, I had to adjust some of the readings and course materials, but I felt comfortable making a basic assumption that some of the students would have at least passive experience with or knowledge of the Infodemic that they could relate to, even if it was likely they would not be acquainted with the underlying concepts or related scholarship. My main expectation was that the students be willing to entertain ideas and perspectives that they may not agree with or even find ridiculous, allowing for exploration that they may not get in other required courses. The lessons were delivered through interactive lectures and discussions, and assignments included weekly forum posts and a scaffolded term paper on the student’s choice of topic.

The main information literacy assignment was a Group Analysis Project, where students were assigned to groups to work on a semester-long writing and source analysis exercise using a generative AI program. Each group created a 1,000-1,500 word essay on a topic related to some aspect of the Infodemic. Their instructions to the AI application required that the essay incorporate and cite the sources it used to compile the essay content. Groups then checked the veracity of the essay and tracked down the sources to determine whether they were truthful, authoritative, and credible using a methodology of their choosing to analyze the content, structure, and meaning of the generated essays (SIFT, CRAAP, PROVEN, etc.). One of the course meetings featured a lesson with a librarian colleague looking at ways to map different analytical methods to the ACRL Information Literacy Framework. Students then organized their findings into a critical report and presented as a group on the AI tool that was used, the analytical approach employed, and any other findings or observations about how these types of technologies fit within the larger notion of the Infodemic.

Most students seemed keen on maintaining a position of measured skepticism, while trying not to slip into a state of paranoid cynicism. As they learned in the course, an Infodemic of some type has always been with humans since we developed language, and our ability to comprehend it, worry about it, and mitigate it, is constantly refreshed through subsequent waves of information communication technology development. The students are not intimidated by this latest wave of technology in a way that older generations are. They are also open to new ideas and really took to the notion of cognitive authority, especially as it relates to trust. Students were encouraged to always think about who they allow to enter and remain within their sphere of cognitive authority, and for several students this seemed far more important than any information literacy instruction or methods, government regulation, or industry safeguards, because it actually makes people think about who they should and should not trust. It also helps one discern between fact and opinion, what is a compelling argument vs. what is complete nonsense, and what is a reasonable standard of evidence that might change one’s viewpoint on a given topic.

With the Group Analysis Project and the other assignments, the students detailed significant levels of exposure to the Infodemic and a commendable awareness of the ways it has affected their lives. Several students demonstrated a receptiveness to the various strategies and methods that the LIS profession has developed to mitigate the Infodemic but expressed uncertainty over their efficacy in the long run. Because when it comes down to it, information literacy instruction is often limited to circumscribed audiences and it is very difficult to assess its impact, especially when the susceptibility to and reach of the Infodemic is nearly universal. After all, most people believe in some conspiracy theory, most of us are more than willing to accept propaganda that goes along with what we already believe, we have all likely shared disinformation of some variety, and sometimes we are just wrong about what we say and write.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 pandemic loomed large in the students’ experience. Their writing and the group discussions on this topic were among the best and most meaningful activities of the course. A lot of it was heartbreaking: family disagreements over vaccinations or masking; isolation from friends and social activity during these formative years; living lives more intensively online within a protective bubble that was both physical and virtual, then being thrust back into an environment that no one could guarantee was any safer or better. For them, the pandemic and its fallout is the Infodemic, and it will shape their existence in ways we will not be able to fully comprehend for many years to come. All the issues of information consumption, technology, democracy, and the future were bound up in these communications, and I can only imagine how I would react if I was in their position–shifting into adulthood at such a contentious historical moment.

However, I can confidently say that I am not worried about them. They will all be fine and I think they will see in their lifetimes, even with all of the challenges and complexity, something approaching an equilibrium and stability that seems so tenuous in the present. Their experience of the Infodemic will form the basis of their resilience. I see our role as information professionals and the role of information literacy as essential to building social trust on that foundation of resilience wherever we can, but this is an uphill battle: it is difficult to stay informed, it is hard work to change minds, and it is impossible to reach everyone. But where there is trust, there is hope, so we must ask ourselves: how do we approach and apply information literacy in ways that inspire trust? How do we help ensure this carries forward beyond our initial and fleeting points of contact with those bringing us into the future?

iREAD Summer Reading Programs

iREAD Summer Reading Programs Latest Library JobLine Listings

Latest Library JobLine Listings