April 2018 | Volume XXXVI. Issue 2 »

Censorship: Looking in the Mirror

March 26, 2018

Dennis Krieb, Lewis and Clark Community College; Emily Knox, the iSchool at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; and the ILA Intellectual Freedom Committee

Aristotle once said that knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom. Looking in the mirror can be difficult at times. The mental image of our appearance doesn’t always match the reflection we see when brushing our teeth, washing our face, or combing our hair (provided there is something up there to comb). The same analogy can be made for us as librarians. What we believe to be an accurate reflection of our profession may not be completely accurate.

The concept of intellectual freedom is indelibly linked to librarianship. It is a belief that is enshrined in the ALA Library Bill of Rights and moves our profession to vigilance and advocacy. But how do we know if our own personal biases

as librarians—latent or otherwise—encroach upon intellectual freedom?

The Illinois Library Association’s Intellectual Freedom Committee (IFC) began planning a survey to explore the issue of self-censor-ship among Illinois librarians in 2015. The overarching research question of this survey would be to better understand if, and to what extent, self-censorship was being practiced in the selection and purchase of materials. Permission to adapt survey questions from the research article, A Study of Self-Censorship by School Librarians, was granted by the article’s author in developing the IFC Self-Censorship Survey (Rickman, 2010).

IMPLEMENTING THE SURVEY

In March 2017, the IFC Self-Censorship Survey was electronically submitted to members of the Illinois Library Association (ILA), Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois (CARLI), Illinois School Library Media Association (ISLMA), Reaching Across Illinois Library System (RAILS), and Illinois Association of College and Research Libraries (IACRL). Of the 520 responses received, the majority (71%) came from those working in a public library. Respondents from independent not-for-profit academic libraries (6%), high school library media centers (5%), community college libraries (4%), and academic libraries in public universities (3%) rounded out the top five response groups by library type. Only those respondents indicating a role in the selection of library materials were asked to complete the survey.

The IFC Self-Censorship Survey was developed around two general themes: internal and external factors that could potentially play a role in self-censorship. Internal factors are personal biases held by a librarian about an item’s content or authorship that would preclude the item from being selected for a collection. Examples of internal factors included explicit language, images, political and religious views, and controversial themes associated with an item. A total of 18 questions were related to internal factors.

External factors explored the impact of outside pressures in the selection of library materials, either real or anticipated. Examples included pressure from parents, students, colleagues, administrators, and community groups. Twenty-one questions associated with external factors were asked on the survey.

A QUICK LOOK AT THE METHODOLOGY

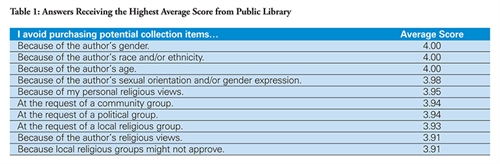

Because the size of the IFC Self-Censorship Survey data set was so large, the IFC decided to limit the initial step of its research to only respondents from public libraries. To provide a method for assessing the survey answers, a score was assigned for each answer that responded to the question prompt, “I avoid purchasing potential collection items….” A score of 4 was assigned for an answer of “Never,” 3 for “Sometimes,” 2 for “Frequently,” and 1 for “Always.”

SOME INTERESTING FINDINGS

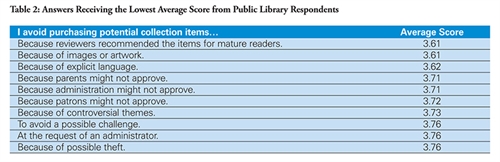

Table 1 shows the top ten answers receiving the highest average scores. This table represents internal and external factors that have the least impact upon self-censorship. Table 2 displays the list of factors with the lowest average

scores and greatest potential for self-censorship.

Table 1: Answers Receiving the Highest Average Score from Public Library

Table 2: Answers Receiving the Lowest

Average Score from Public Library Respondents

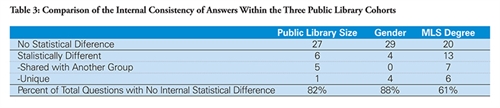

Three public library cohorts were also selected from which to compare the internal consistency of survey answers. These cohorts were based on 1) the size of the public library, 2) the gender of the respondent, and 3) whether the respondent had a master’s degree in library science (MLS). The purpose of this test was to assess the level of agreement within each of the three cohorts on self-censorship factors. Thirty-three questions were used for this test.

When looking at the internal consistency of how each of the three public library groups answered the 33 questions, the group based upon the gender of the librarian was the most consistent. Only four questions were found as having a statistically different response based upon the gender of the librarian. The second group with the most consistent answers was the cohort based upon the public library size. Six of the 33 questions were found to have answers that were statistically different. The group with the least amount of internal agreement was the cohort based upon whether the librarian had an MLS. Of the 33 questions answered by this group, 13 were statistically different. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-tests were used to test responses for statistical differences using an alpha of .05.

Table 3: Comparison of the Internal Consistency of Answers Within the Three Public Library Cohorts

JUST THE FIRST STEP

A presentation discussing this survey was presented at the ILA Annual Conference in October, 2017. The session, Censorship: Looking in the Mirror, was presented by Dr. Emily Knox from the iSchool at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and an author of this article. Feedback from the presentation audience provided insightful questions and diverse reactions. Of particular note were the varied reactions of children’s librarians to some of the findings.

As mentioned previously, there are still many findings yet to be discovered in the IFC Self-Censorship Survey data. The IFC plans to continue its research and share its findings in future editions of the Reporter. Thanks to all of the IFC members for their hard work over the past several years on this project, with special recognition to IFC chairs Nancy Kim Phillips and Rose Barnes for their leadership in seeing this project through, and Dr. Emily Knox for her service as a consultant.

SOURCE

Rickman, W. (2010). A study of self-censorship by school librarians. School Library Research 13(10). Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/aasl/slr/volume13/rickman

iREAD Summer Reading Programs

iREAD Summer Reading Programs Latest Library JobLine Listings

Latest Library JobLine Listings