March 2021 | Volume XXXIX. Issue 1 »

Reaching Underserved Communities through DEI Training

March 1, 2021

The ILA Diversity Committee

In September 2020, ILA’s Diversity Committee conducted a survey to identify ILA members’ diversity training needs. At the 2020 Annual Conference, they held a listening session to obtain additional feedback. This article summarizes the survey results and notes from the breakout sessions. It is intended to inform the ILA Executive Board, forums, and committees’ work as they more fully integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) into ILA activities and initiatives, in keeping with the ILA strategic plan goal for “A culture of diversity and inclusion in the profession.”

Additionally, the survey was created in response to significant recent social upheaval and serves as an opener for much-needed dialogue that confronts the lack of diversity in the services that libraries provide, emphasizing the need for training for Illinois library staff.

DEMOGRAPHICS

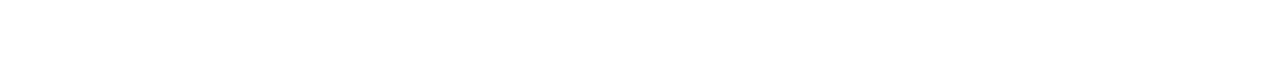

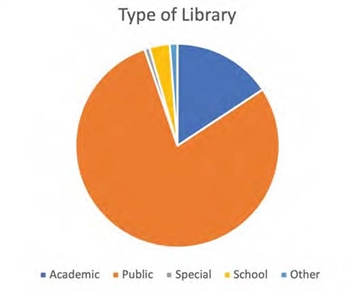

A majority of respondents in our survey work in a suburban public library. With most Americans living in suburban areas, the nation has become more diverse than ever (Micklow, 2014). With these changing demographics, libraries are challenged to meet the needs of these diverse populations.

Engaging everyone in an ongoing conversation to bring to the forefront the very issues that divide us all is paramount. Participants in the survey and listening sessions agree, but some respondents admitted that they could face opposition from their communities and fear backlash against any DEI training. False ideology regarding diversity training has promoted the belief that discussing diversity is unpatriotic and counterintuitive to its purpose and somehow vilifies white people. One participant in our survey responded that they did not want to feel guilty for being white due to diversity training. For this reason, the scope of diversity, though broad, must be clearly defined to be understood by those who feel they are being denigrated through this training. Diversity training, viewed by some as divisive and now prohibited at the federal level (Exec. Order No. 13950, 2020), can allow ILA members to reach underserved communities more readily by providing insight into users' needs. Moreover, it is a useful tool in creating a more inclusive and engaging culture.

DIVERSITY DEFINED

The term diversity, or differences amongst a group, is a broadly used word that gets thrown around frequently. Over time its meaning has evolved since there are many ways that people are different from one another (Kreitz, 2008). Staff with diversity skills can be flexible, engaging, more insightful, and more accommodating when it comes to meeting diverse users' needs, translating to high-value services for the community, and fostering an environment where everyone feels valued. To tackle the task of meeting the needs of communities whose differences vary widely, we asked ILA members to identify underserved communities and the factors that contribute to their lack of service.

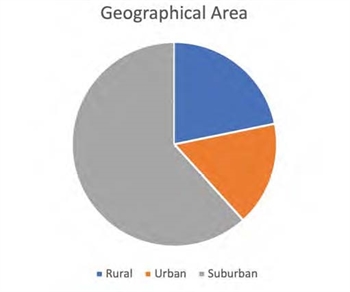

Non-English speakers, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and Latinx were the three leading populations that were identified as underserved communities. The lack of services among these groups could stem from various issues that may limit their ability to utilize library services. Factors such as money, small staff size, location, language barriers, and digital divide were identified as service barriers.

Illinois librarians and staff must have the confidence and knowledge to understand this complex issue and meet the needs of underserved communities where they work.

BARRIERS TO TRAINING

Some common themes emerged when looking at the survey responses and the notes from the ILA Voices breakout session from the conference. Attendees identified multiple barriers to DEI training. Unsurprisingly, COVID-19 was often mentioned as a barrier. With library closures, fewer staff members, reduced capacities, decreased budgets, and extensive safety measures in place, receiving diversity training is limited as organizations are addressing the immediate needs related to the pandemic.

Perceived diversity, equity, and inclusion training needs were addressed in the listening sessions as well. Attendees highlighted issues that are experienced in the library community: many well-known and some less so. Help with recruiting and retaining diverse staff, mentoring, and merit-based hiring was suggested. This is reflective of the lack of diversity among library staff, which has been a problem for some time, even as communities have become more diverse (Larsen, 2017).

ONGOING TRAINING NEEDS

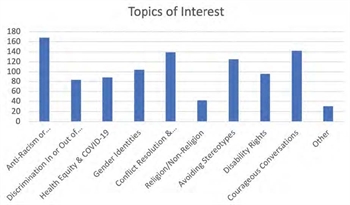

A consistent trend in responses was the desire for more diversity training opportunities for all staff, not just librarians, but also ongoing training in servicing different communities. Respondents indicated a preference for web-based training that includes a variety of in-depth on-demand diversity information. Of particular interest were topics covering anti-racism, unconscious bias, courageous conversations, and conflict reduction and resolution. The majority of respondents reported received diversity training as an optional course, rather than required, and accessed their training through their employers, ALA, ILA, or RAILS.

It is clear from the survey and listening session that ILA members do not consider themselves to be beginners in learning about diversity. They seek a more intuitive approach to learning about diversity that synonymously provides practical information that can put to use right away. Two respondents suggested that high quality, expert training performed by non-library professionals was needed.

These issues are made worse due to the pandemic, which has changed much in the way we work and made it more challenging to receive the training needed to reach underserved communities. However, for diversity training programs to succeed, management must be involved at every level (Larsen, 2017). Some respondents stated that their library’s administration has not demonstrated the value of diversity, equity, and inclusion and has not begun a discussion among staff to generate awareness, interest, and support.

The problem with diversity training in the past has not been that others have not been aware; more depth is needed. Moreover, diversity training has been inconsistent and not integrated into other activities.

The unfortunate aspect of diversity training as it has existed in the past is that it does not guarantee change. However, change can only happen when a library administration institutes a training program tailored to their specific staff needs. Additionally, a diversity training program is most effective when there are well-defined outcomes for change (Lindsey, 2017).

Though every library organization varies in the degree to which it values diversity and the amount of change they engage in to support it (Kreitz, 2008), practical, engaging, and relevant diversity training, can better equip ILA members to become culturally competent and develop insight into the needs of underserved communities.

During the ILA Voices breakout session, participants were asked to provide examples of effective methods that libraries had used to make their services more equitable and diverse. Libraries going fine-free, outreach to shelters, and making WiFi accessible outside the library were but a few of many instances mentioned that libraries have successfully demonstrated that diversity, equity, and inclusion can be woven in library services.

CONCLUSION

ILA members have voiced a desire to see much more relevant, high-quality, practical, and engaging diversity training offered. This demonstrates the value of creating an inclusive culture by drawing people from different backgrounds, cultures, experiences, and points of view to meet the needs of their increasingly diverse communities. With the changing demographics of our communities, becoming culturally competent is vital in fostering an environment of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The ILA Diversity Committee includes co-chairs Jordan Neal and Hannah Rapp, and members Katrina Belogorsky, Monica Boyer, Brittany Coleman, Lindsay Holbrook, Mary Ann Lema, JJ Pionke, Rosie Williams-Baig, and Megan Young. The Committee’s Executive Board liaison is Jennifer M. Jackson, and the staff liaison is Tamara Jenkins.

Works Cited

Exec. Order No. 13950, 85 Fed. Reg. 188 (September 28, 2020).

Kreitz, Patricia A. (2008). “Best Practices for Managing Organizational Diversity.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 24(2), 101-120. doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib. 2007.12.001

Larsen, Sara E. (2017, December 7). “Diversity in Public Libraries Strategies for Achieving a More Representative Workforce.” Public Libraries Online. https://publiclibrariesonline.org/2017/12/diversity-in-publiclibraries- strategies-for-achieving-a-more-representativeworkforce/.

Lindsey, Alex, et al. (2017, July 28). “Two Types of Diversity Training That Really Work.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/07/two-types-of-diversity-trainingthat- really-work.

Micklow, A.C., & Warner, M.E. (2014). Not Your Mother’s Suburb: Remaking Communities for a More Diverse Population. Urban Lawyer, 46(4), 729-751.

iREAD Summer Reading Programs

iREAD Summer Reading Programs Latest Library JobLine Listings

Latest Library JobLine Listings